Visiting the everlasting turmoil caused by Hurricane Katrina to the youth of St. Bernard Parish, New Orleans’ often forgotten neighbor.

The days that crept behind August 29th, 2005 were perfectly ordinary. In St. Bernard Parish, the children of the district finished their second week of the academic year, their school supplies still unblemished from wear and tear. On Friday, August 26th, teachers at each school scripted next week’s curriculum on their respective classroom chalkboards, fathers prepared their fishing tackle boxes for an early morning on the bayou, and mothers fantasized about the free time they would relish after dropping their kids off at catechism.

When news hit that a storm was developing in the gulf, these attitudes went unbothered. For residents of St. Bernard Parish, this news often meant that they would have to hastily prepare their homes for window damage with the slight chance of a minuscule amount of water creeping under the gap of the front door. Most families boarded their windows with spare lumber in their sheds and picked up sandbags distributed by the St. Bernard Parish Government to place at the feet of their doors. Some families didn’t prepare at all, as these developments were usually false alarms and their customary lives would continue as soon as next week; barricading the house for hurricane impact was a waste of time and effort.

The kids of the parish shared this sentiment. With the responsibility of evacuation on the laps of the adults, nothing stood in the way between the youth and their uninterrupted outdoor scenes of jubilation. On the morning of August 27th, skateboards hit the pavement down Livingston Avenue and bicycles carved dirt paths along the levee adjacent to St. Claude Highway. The neighborhood pools at Buccaneer Villa Swim Club and the St. Bernard State Park hosted birthday parties for those lucky enough to take refuge from the sweltering August heat. Swing-sets and monkey-bars at Sydney Torres Park squeaked from extended use and children would grunt with laughter as they fell from both devices onto the rough of the mulch. It was the calm symphony before the storm.

When the streetlights glimmered yellow and it was time to come inside, the youth got back on their bikes and dapped their friends goodbye, expressed “See ya Tuesday!” and darted home. At this time, the neighborhood pools treated their waters with extra concentrated doses of chlorine to withstand the evacuation closure, just in case. The swingsets came to a withering halt.

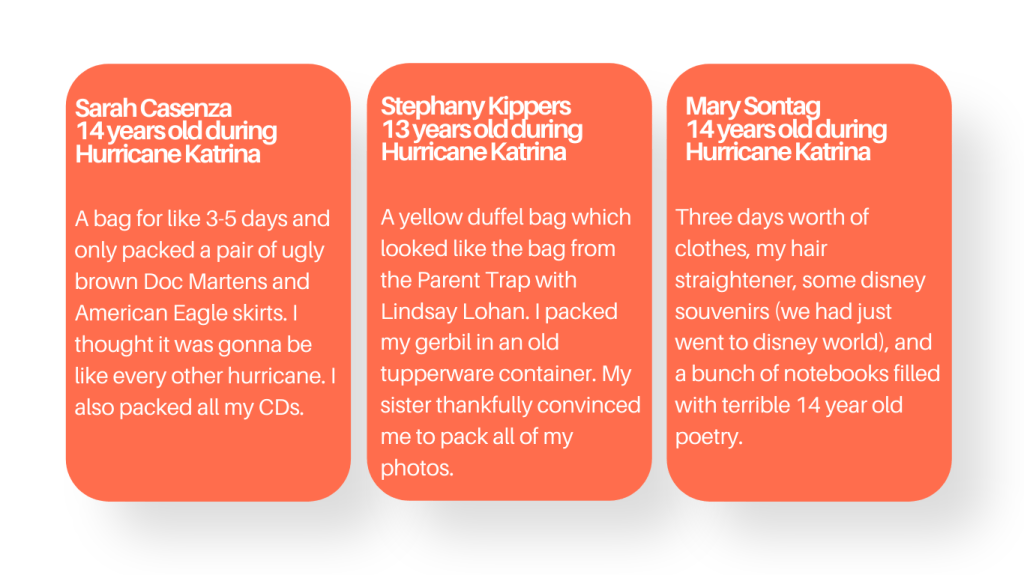

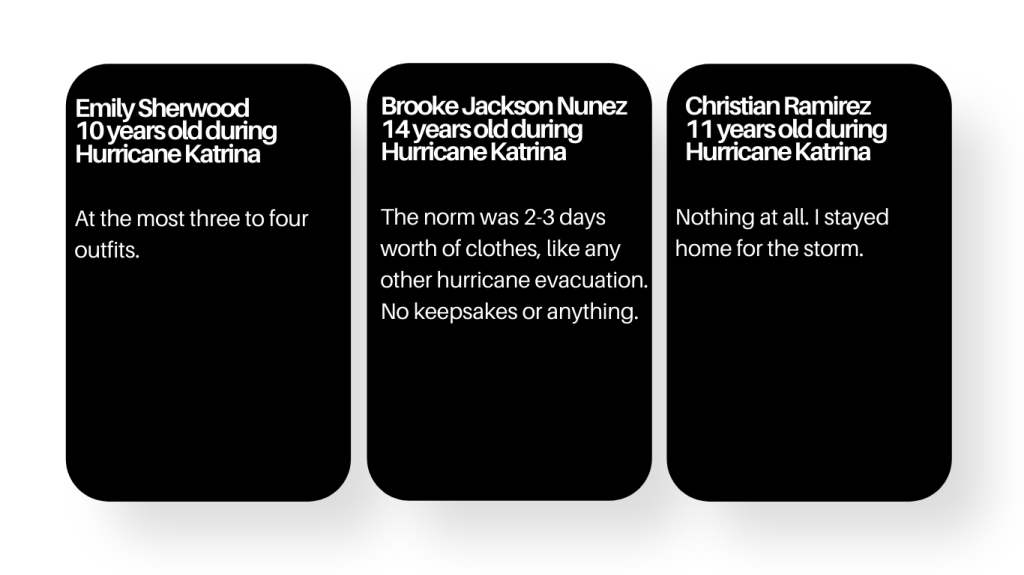

Upon arriving home, the kids of the parish were sanctioned by their parents to pack for the evacuation. With luck and laziness on their side, most bags were packed haphazardly: two pairs of shorts, three t-shirts, four pairs of underwear and socks, one pair of tennis shoes, a CD player, hair straightening iron, Nintendo DS, and toothbrush. It was everything they needed for a few days away from home.

The very next day, on August 28th, they realized that they under-packed. At their evacuation zones, from aunts and uncles’ houses on the northshore to motels in central Louisiana and Mississippi, television screens flickered panic across the gulf coast. Hurricane Katrina strengthened into a Category 5 storm, and it was headed straight for St. Bernard Parish. By the next day, those same screens flashed aerial imagery of their houses completely engulfed in floodwater. The pavement: invisible. The schools: flattened. Their childhood: demolished. Seeing their friends on Tuesday was no longer a reality. They may never see them again.

The voices that follow serve as a gateway into the lives of the youth of St. Bernard Parish, all of whom survived the costliest natural disaster to ever hit the south. Costliest, carefully chosen, as Hurricane Katrina cost them their past, present, and future.

Escaped Adolescence

It takes immense grit, strength, and heightened emotional intelligence to deal with the aftermath of an apocalyptic storm. It is undeniably true that the youth of St. Bernard grew up quicker than most; due to the hostile conditions around them, they had no choice but to mature at a rapid speed. Some may argue it’s a survival instinct, while others may suggest it’s a learned behavior.

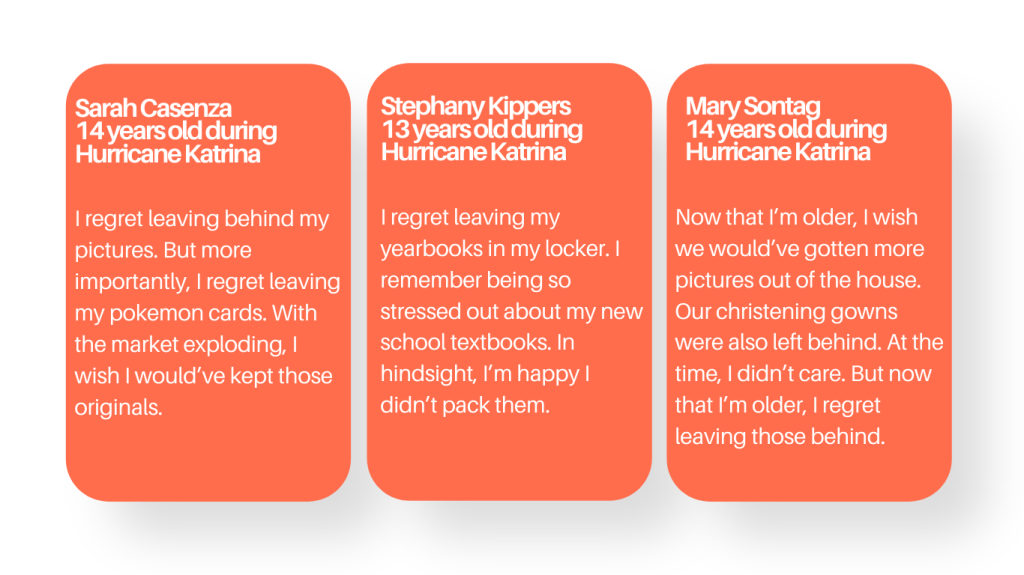

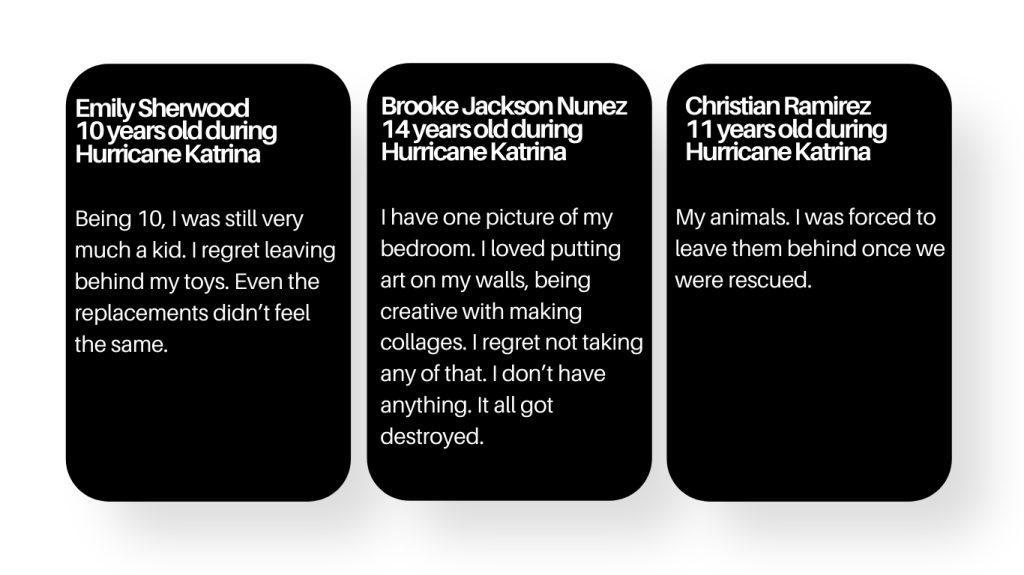

Regardless of philosophy, the youth all endured these shared hardships together. Twenty years later, they reflect on what happened and what they wish they could change.

What did you pack with you when you evacuated for the storm?

What do you regret leaving behind that you still think about?

A Trashbag, A Truckbed, An Empty House:

from the lens of Nichole Acosta

In the fleeting moments before the storm, packing a well-prepared suitcase is a luxury not everyone can afford. For Nichole Acosta, thirteen-year-old resident of Violet, packing was hardly an option.

“I grew up in a very low-income household, so it was a lot of us in one home. We weren’t planning to evacuate, so we hadn’t packed anything at all. And then the morning before the storm was supposed to hit, my mom and my dad were like, oh, we gotta get out of here. Like, we gotta go. I think it’s gonna be bad.”

With twenty minutes and a kick into pure survival mode, Nichole had to act quickly.

“My parents gave us each a trash bag. Like, the thirteen-gallon trash bags you would use in a kitchen garbage can, and told us we have twenty minutes to just throw some clothes and shoes in there, so that’s all we could take with us. We weren’t allowed to take any of our personal effects or anything like that.”

A family of ten, Nichole’s family swiftly strategized how they would make it from Point A to Point B, wherever that was. That morning, ten of them piled in a small truck with their trash bags and got going, including her severely disabled cousin who relied on constant medical equipment.

With barely any space left in the truck (they had to pack her cousin’s medical equipment and the chargers that power them), Nichole’s family crammed as much as they could in a small truck that had a cab over its bed. Her special-needs cousin was in the back seat of the truck along with her grandparents, her uncle in the front seat with her parents, and then the rest of her family laid out in the back cab of the truck.

They decided to drive west on I-10 to see if they could park at a rest station until the storm was over.

“Traffic was literally at a standstill. I’ll never forget that. People were just parked on the interstate and chit-chatting with each other from different cars, like a hey, you got a cigarette? kind of situation.”

After sitting in traffic for many hours, it was from the back of the truck that Nichole and her family experienced the worst of the storm.

Everybody was trapped in their cars and the storm hit early the following morning. The rain and wind raged on and on. According to Nichole, it felt like it would never end.

“The lightning was so bad. And I remember being so scared in the back of that truck thinking, like, you know, this was it. There’s no way we can get out of this. I prayed and cried that I just wanted to be home.”

Somewhere nested between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, the storm winds finally lifted and the family reassessed their next steps. It was then that they began driving back toward St. Bernard Parish to check on the eleventh member of her family: Nichole’s grandfather, who stayed behind for the storm.

Once they reached the New Orleans metro area, they were met with a roadblock set by Louisiana State Troopers. They weren’t letting anyone in.

“My grandma tried to explain to a state trooper that we have medical equipment we need to get, and that her husband was still there at home with no form of communication. And that’s when he told her, ‘Ma’am, nobody can get in the parish. It’s completely underwater.’ I remember sitting there not understanding what he meant, like, not being able to comprehend.” The state trooper pushed them to turn around, “or else.”

With no money, no food, and nowhere to go, they decided to turn around and start driving toward Lafayette, finding a place of rest at a nearby truck stop. They stayed there for nearly three days, resting on arm chairs in the truck stop’s lounge.

However, tragedy continued to strike. The backup batteries for her special needs cousin were at the end of their life. In a panic, her grandma called the local hospital in Lafayette asking for help. If his medical machine stopped, he could potentially pass away within hours.

Less than an hour after that phone call, a Lafayette news crew showed up to the truck-stop to interview Nichole’s family.

“At that point, it was the most surreal experience of my life because it was all happening live. I remember at the time I felt annoyed, like, do I really have to be on TV? This is so dumb.”

Fifteen minutes later, the parking lot of the truck stop flooded with locals.

“It was so surreal and so humbling. People drove from Breaux Bridge and the surrounding parishes. It was unreal. I felt very panicky because there were so many people. I mean, I’m talking, you couldn’t move crowd of people. They began throwing change and dollar bills at us. I felt like a circus freak. They were coming up to us and touching our heads to, like, pray on us. I remember feeling very unsafe and uncomfortable because the story had just provoked a bunch of people, you know? They were even shoving loaves of bread in our hands. I was wearing a hoodie and a pair of jeans, and I didn’t even have a shirt under the hoodie because I had nothing clean. And they were shoving money in the pockets of my jeans. I felt very violated because it was just so uncomfortable. I get they were coming from a good place, but being so young, it was a very scary moment for me. I just didn’t understand.”

While she wasn’t used to receiving such generosity from people, the kindness from strangers didn’t stop with money and loaves of bread. An anonymous real-estate agent from Breaux Bridge offered the best possible scenario for Nichole’s now homeless family: rent-free shelter.

“It was a huge two story, six bedroom home. It was absolutely beautiful. He said, ‘Hey, I want y’all to come stay in this empty home. There’s no reason your family should be homeless like this, especially with a special needs person. I was planning to sell it. It’s already cleared out. Come on over.’”

The family left the truck stop in Lafayette after three days with no food and experienced a whole new gradation of generosity from the community of Breaux Bridge.

The community showed up daily with groceries and clothes, the local McDonald’s dropped off food, and even the local Cox Cable Company came and hooked up a TV at the house to help keep them entertained. Select members of the neighborhood also took them to Walmart to get basic supplies such as shampoo and conditioner.

“It was unbelievable. It was absolutely unbelievable. It was probably the most beautiful community I’ve ever experienced.”

Taking two weeks to settle down, Nichole started school in Breaux Bridge, but adjusting to a new school proved to be overwhelmingly difficult. After a week at her new school, the reality of everything that had happened started to sink in.

Her grandfather, who stayed behind, was still missing.

Through neighbors, they discovered that their house had completely lifted off of its foundation, hit a grove of trees, and snapped in half. “Split right down the middle.” After weeks they finally reached contact with her grandfather.

When the levees broke and the floodwaters started to rise, he was forced to swim to the Mississippi River levee, where he camped for four days with no food or water, until a rescue crew arrived. From there, he was sent to Texas, and then to Picayune, Mississippi, with family.

Nichole’s family decided to join him out in Picayune until they could figure out their next steps.

For Nichole, it felt like a breath of relief.

“As much as I loved the community of Breaux Bridge, I hated being labeled a victim. I couldn’t do anything without having all of these people stare at me. When I would go to the local Walmart, I could hear them whispering and I could see them staring. And I hated it. It made my skin crawl. I just wanted to go home and take a shower.”

While the intentions of the Breaux Bridge locals seemed earnest in nature, some struggled with boundaries.

“People would just come up and ask you things like, What all did you lose? Did you lose any family members? In what sane world do you think it’s appropriate to ask a child did you have any family that drowned? It felt like they didn’t really understand that we were real people.”

These struggles carried into the classroom, in which local students failed to grasp the magnitude of what Katrina victims had experienced.

“While sitting in the back of the classroom, another kid was like, ‘I hate going to school. I wish it would flood here and then we wouldn’t have to go to school!’ I remember holding my breath, and then the teacher pointing me out. So then, of course, the entire classroom turns to look at me, and then there’s this awkward silence of, oooh, yeah. They just lost everything, and they’re still here in school. I wanted to die. I wanted to die. I just wanted the ground to open up and swallow me.”

Moving to Mississippi also meant changing the dynamic of her current home environment, which had shifted due to the storm. With her family not used to having a large amount of cash on hand, Nichole began to witness a side of her family members she hadn’t seen before.

Instead of taking account of what they needed to survive, certain family members began to let their greed get the best of them. At one point, her mother decided to take matters into her own hands by using Nichole as an objective scapegoat to receive more money.

“It was a very gross situation. I wore the same bra for the entire time because there somehow wasn’t enough money to buy me a new one. And it had, like, rubbed my skin raw because of the wire in it, and I was actually bleeding. I hadn’t said anything because I was embarrassed. My mom forced me to raise my shirt up while they were all arguing about money, like, Look at her! I felt very used at that moment, and it just put a sour taste on a lot of family members. And we just never recovered, honestly, after that. Even now, years later, I have no contact with almost my entire family.”

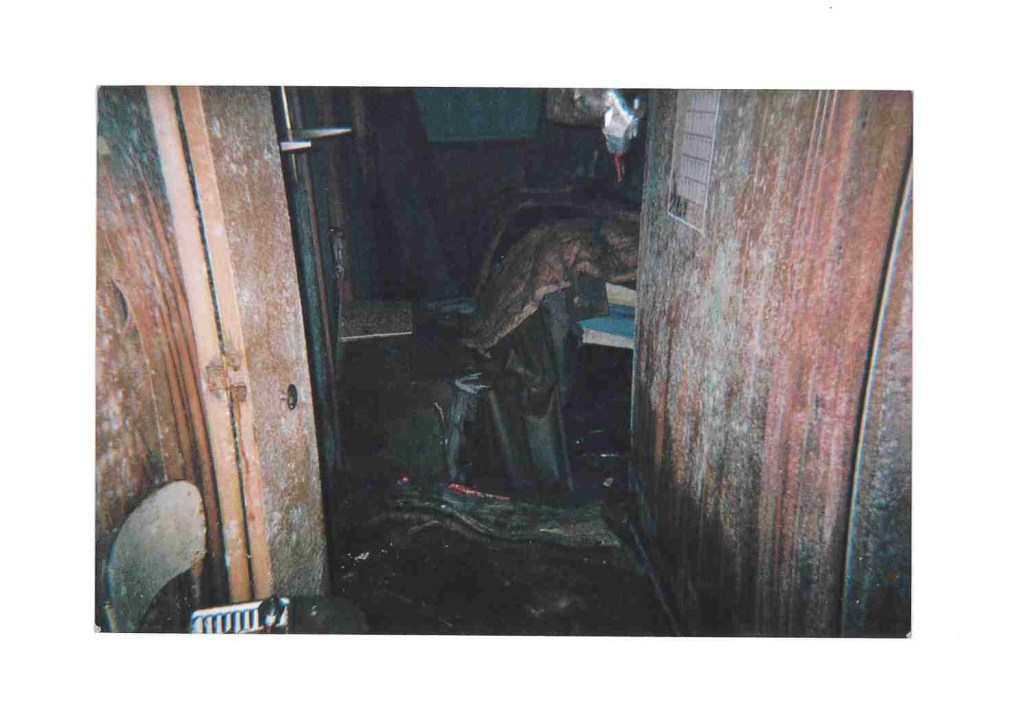

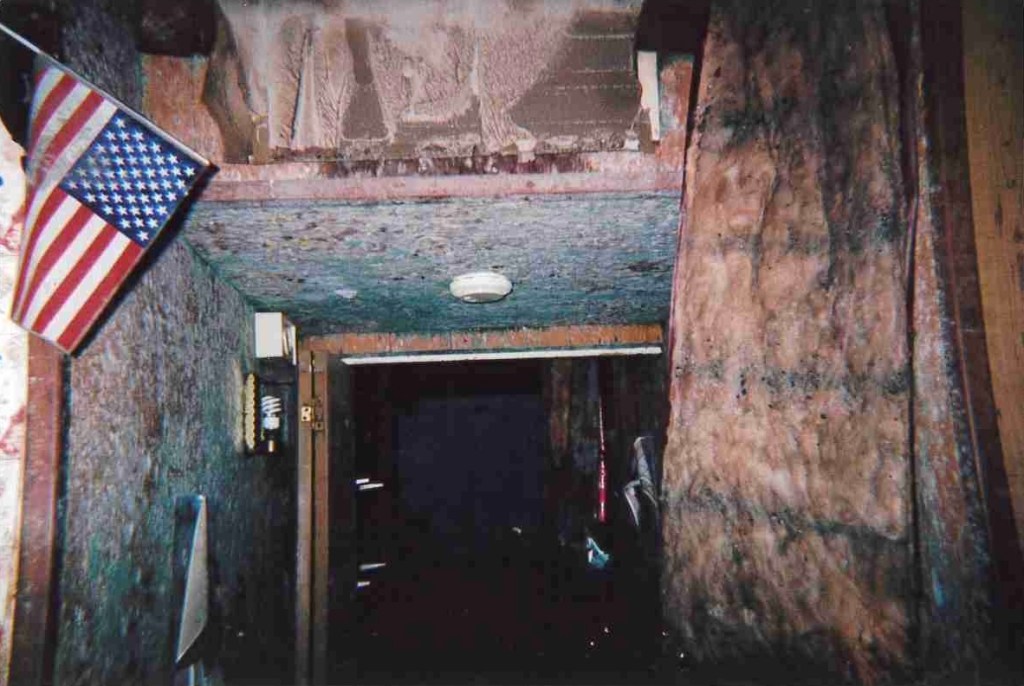

Upon moving to Picayune, the family waited for FEMA to provide a trailer to set on the same land that had been in her family for generations. Before that, Nichole and her family made trips to their house in Violet to assess the damage and salvage anything that could have potentially survived the storm.

“The first thing I noticed was the smell. It had an aftertaste of a decaying bayou. We had biohazard masks to wear and the smell seeped beyond the masks. There was just mud everywhere. We had to go through the oak grove tunnel of trees on St Bernard Highway to get to my house, and I remember seeing a dead horse that drowned in the storm. Seeing that made me think about the people who stayed who might still be dead and lifeless in their homes.”

The horse was an omen for what she would witness when she made it to her house.

Nothing was salvageable.

Before the storm, Nichole was vendetta free; throughout her childhood, she would move from house to house, often facing eviction from her family being unable to pay rent or utilities. Due to the constant change in her life, it was easier for her to let comments that people would make about her go. She also didn’t feel the need to get attached to material items. After the storm, that all changed.

“After losing everything in Katrina, I started to get attached to items, and it was difficult for me to throw things away. The anxiety at the idea of, like, throwing small things away was overwhelming because I would never see it again. And it’s so weird because it would be something as silly as a pair of shoes or a shirt. Before Katrina, I couldn’t care less.”

That was the old Nichole, before she legally changed her name. After years of psychotherapy, Nichole decided that in order for her to move on from her past, it was in her best interest to change her legal identity. In doing so, she’s been able to live a life where she can throw away old shoes and shirts again.

“Going no contact with my family was one of the hardest things ever. Even now, they try to still get in touch with me, but I had to let all of that go. And now the new Nichole is happy. I’m engaged, I have my kids, and we have a home. It’s a nice home.”

Nichole now lives with her fiance and kids in St. Bernard Parish where her children participate in recreational sports, a luxury she couldn’t afford to do herself when she was young.

“It almost seems like I’m a completely different person.”

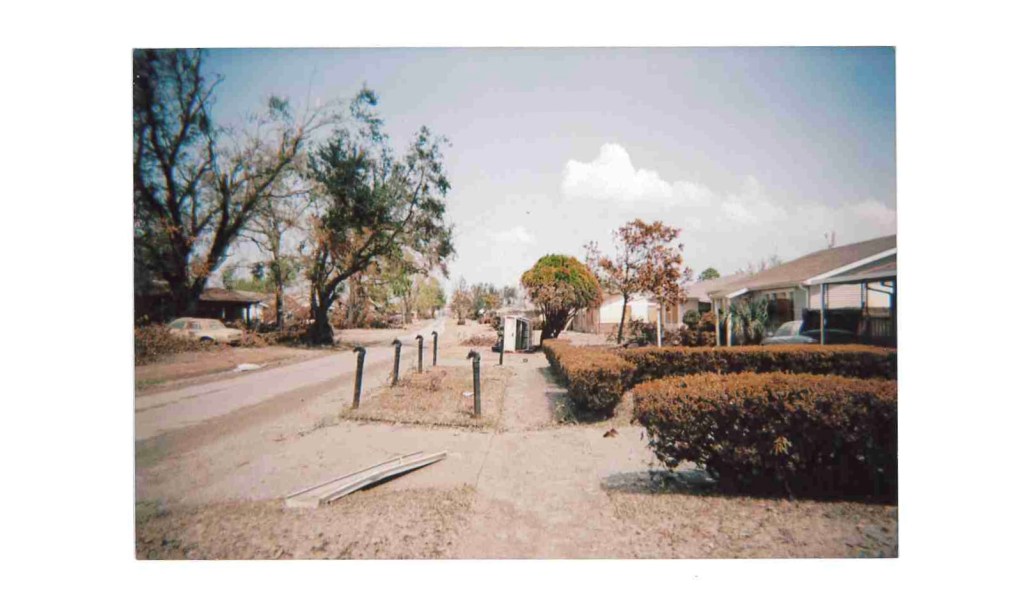

Every Vacant Lot Tells a Different Story

In 2005, Buccaneer Villa was a prime real estate goldmine in St. Bernard Parish. The subdivision, adjacent to Sidney Torres Park, the parish’s largest public park, boasts its own country club (Buccaneer Villa Swim & Tennis), its own court of mini-mansions in Queens Court, and recreational sports park, Vista. Before Katrina, the subdivision was home to 983 residential structures. Today, it’s barely a third of that.

(Source: Google Earth)

The slides above substantiate that even twenty years later, once prosperous subdivisions in St. Bernard Parish still struggle to reach the same capacity as before the hurricane. After the water receded, the parish waited 5 years to demolish all homes in 2010, leaving behind a vast concrete slab jungle. What exists today is a grassland atop what was once a carefully planned blueprint for suburban utopia. Why would families refuse to return?

Everybody has their reasons, including Juliet Honore and her parents, who lived in the once bustling subdivision.

Through a Whirlybird Hole in Buccaneer Villa:

from the lens of Juliet Honore

On the afternoon of August 28th, 2005, three loud knocks graced the door at 3708 Norwood Drive, a modest ranch home in the Buccaneer Villa subdivision of Chalmette, Louisiana.

Juliet Honore, twelve years old at the time, watched as her father, Stewart Partridge, answered the door. On the other side stood a man in a full wetsuit garb with scuba diving flippers and a gun on his hip. It was an officer from the St. Bernard Parish Sheriff’s Department.

“I was really young at the time, and I remember thinking, Is that Scuba Steve from Big Daddy at my front door?” Juliet recalls.

The officer warned Stewart and Caroline, Juliet’s stepmother, that this storm is going to be worse than what everyone anticipates and that it’s in their best interest to evacuate. Her parents nodded and the officer left, the door closing behind him.

With no money for a hotel or resources to evacuate, Juliet and her family decided to stay behind.

Heeding the officer’s warning, she watched as her dad and stepmom scrambled to get the house in order, preparing for the worst.

“My stepmom had these porcelain dolls, and I remember her putting them on top of the fridge along with other things that were valuable to them. We had two chihuahuas, a calico cat, a goldfish, and a guinea pig. So we had to improvise how we were going to take care of them in case the house did start to get a little water. We placed my guinea pig into a laundry basket and we got the attic prepared. My dad specifically put an axe and some life jackets up there.”

These tasks were handled through gentle fits of laughter, as it seemed ridiculous that the water would ever rise high enough to warrant escape through the attic. Even so, her dad cautiously began placing their belongings up there, including the family goldfish and some canned foods that Caroline had purchased. Just in case.

Juliet and her family prepared lunch as Bob Breck, chief meteorologist and local weather prodigy at WVUE, flashed across their television screen and provided his grave warning to all locals. Shortly afterward, Juliet joined her father as he walked around the neighborhood, surveying the wind and taking exterior photos of their home for insurance purposes. For the most part, the weather was calm.

That all changed by dinnertime.

“I remember my stepmom saying we should’ve left. Even with the little resources we had, we should’ve left.”

The streets began to flood, but not enough to cause panic, even if it was entirely too late to evacuate. At this point, the camera crews streamed live shots of people still drinking at bars in the French Quarter, which seemed relatively unscathed in comparison to the streets of Chalmette.

This seemed normal for New Orleans, storm or no storm.

At 8:00PM, Juliet jumped as she noticed the motion sensor on her front porch began to flash.

Stewart darted toward the front window to investigate, and as he pulled back the curtains, they realized this was no ordinary storm. The water on the other side of the window was knee-level.

“My step-mom was in disbelief. She was like, ‘No. If there was water outside the window, it’d break the window!’”

Her eyes did not deceive her; the water on the other side continued to rise, and it slowly began to seep from under the gap of the front door. Shortly after, the power went out.

“We were literally blindsided at this point because we couldn’t hear or see anything. We didn’t know what was going on. All we knew was the storm was starting to approach onshore. And at that point, my dad’s like, ‘You know, I’ve never seen this much water outside since Hurricane Betsy.’”

At 2:00AM, floodwater continued to stream from under the front door, but it seemed stabilized. Overwhelmed with exhaustion, the family retreated to Juliet’s bedroom for rest, as it was the closest to the attic door. After her father pulled the attic door down, they dried their wet ankles and climbed into Juliet’s bed for a few hours of shut-eye as the trees around them began to splinter and collapse.

A few hours later, Stewart woke to use the bathroom. At this point, there was a foot of water in the house. Desperate for any sign of an update, he turned the volume up on his battery powered radio. What he heard next shifted his fears into reality.

The Industrial Canal Levee in the Lower Ninth Ward had breached, and the water had nowhere to go except St. Bernard Parish.

In a swift panic, he instructed Caroline and Juliet to grab the animals and head up to the attic.

“It was hours just sitting there and just sitting there. And then it’s like, uh-oh. We need to use the bathroom. Where do we go? Well, you can’t see. It’s pitch black dark. We had flashlights, you know, smaller resource ones, not like the LEDs you got today. But, like, you could barely see. So at one point, we were like, well, let’s see if we can go to the bathroom because the toilet was not under completely before when we came up the attic stairs.”

Upon reaching the bathroom nearest the attic stairs, the water had gone up to just below the toilet rim. As each minute passed, the storm surged harder and harder.

“It was so loud outside. So loud. The vibration from the wind against the house made it very hard to hear. It was straight pressure.”

By the time both Juliet and Stewart finished using the hallway bathroom (Caroline stayed in the attic), the front windows in her living room burst open, and the water outside came flooding in.

Juliet rushed up the attic steps, her father behind her, and before she could get to the surface of the ceiling her father pushed her through. Seconds after he reached the attic, the attic stairs slammed behind him. The strong current of the water rushing in from the living room forced the stairs to slap against the ceiling, still unfolded. There was no way to get back down.

Stewart immediately grabbed the axe he stored earlier and began swinging at the roof.

“All my dad kept saying is, ‘We’re not gonna drown. We’re gonna get out.’” Juliet remembers.

As he began swinging the axe at every possible surface of the ceiling in a desperate attempt to create an opening, the wind from the hurricane sucked the whirlybird off the roof. He acted quickly.

“He was a tall, slinky man. He poked his head out where the whirlybird was to look around, and the wind was, like, whipping. I mean, it was whipping. You could just hear how loud it was.”

He looked out, came back down from the hole, and glanced at Caroline in pure awe.

“My dad looked at us blankly and said we should’ve left.”

From the small opening in the roof, he witnessed water up to the rooftops of all the surrounding houses in the neighborhood.

Returning from the hole, he grabbed his axe and began swinging at the same spot the whirlybird was in an attempt to make it larger for his entire family to fit through.

The water began to rise higher in the attic. With the floodwater now at waist-level, the dogs began to swim, the guinea pig began to float in the laundry bin, and the cat was soaked in its kennel.

One by one, Juliet, Stewart, and Caroline made it through the hole and onto the roof with their cat. The chihuahuas floated up as the water rose, and eventually climbed their way through.

Soon enough, the water was high enough to where they couldn’t go back through the hole in the roof. The guinea pig and goldfish didn’t survive.

“There was nothing we could do but try and figure out how the hell we were supposed to get out of there. We heard people screaming for help out of nearby two-story homes and we couldn’t help them. We couldn’t even help ourselves. My stepmom started praying. She didn’t care who she believed in at that point.”

After spending a whole day on top of the roof with no resources, Juliet’s dad noticed a boat that belonged to one of the neighbors floating nearby.

One by one, once more, her family made it onto the boat.

After a day and a half on their neighbor’s boat with no food, water, or proper restroom, a good samaritan with a larger boat drove by. “They had a big enough boat and told us that they were gonna come back for us, and they did.”

Leaving their submerged home behind, they were loaded onto the larger boat. However, another obstacle arose. They were told they could bring their pets on the boat, but the shelter he was taking them to might not allow them.

“What do you do? You just can’t leave them. So we decided to take them with us, but we didn’t know where we were going until they rolled us up to the back of the courthouse.”

At the St. Bernard Parish Courthouse, Juliet and her family said their farewells to their pets, as they were informed that all pets were being transported and housed at the St. Bernard Parish Prison, separate from human contact.

From the third story banister of the overcrowded courthouse, Juliet looked down at the water as it lingered up to the second story. After a day of eating half peanut-butter sandwiches (there wasn’t enough bread available for whole sandwiches), her family was told they would be forced to move to the prison, where there was less water damage and more room for families to spread out.

In true Parish fashion, her family did their best to find comfort in the scenario. “Wherever there was an opening in the jail cell to sit down, you made friends with whoever sat next to you.”

Upon stepping outside of the jailhouse, Juliet witnessed two things she’ll never forget: vicious dogfighting and a giant refrigeration truck containing bodies of the recently deceased.

As people in the jail began to die and their bodies were carried to the refrigeration truck, Stewart anxiously began begging for information on how to get his family out of the jailhouse and somewhere, anywhere, else.

Through the grapevine, they were offered a spot on a barge docked at the Chalmette Ferry to transport them upriver to an undisclosed location, but the barge owner refused to allow animals aboard. Juliet and her family attempted to give what they thought would be a temporary farewell to their fur-babies, but they were denied entry to the area that housed all the displaced animals. The Sheriff’s Department didn’t allow them to see their animals unless they were leaving with them.

“They kept telling us, look, if your dog is here, they have rescue centers that will come in and help reunite you. They had food and water to give them. So we just put it in the back of our mind that this was all that we could do. They told my stepmom there’s a website called Petfinder, and I am 100% sure you’ll be able to find them after this is somewhat situated.”

With no other option, Juliet and her family boarded the privately owned barge and headed up the Mississippi River. The destination? A random, vacant lot on the Westbank. “None of us had ever really gone to the West Bank in general before Katrina, so we really didn’t know where we were going. We just knew we were gonna be better off than where we were.”

The barge pulled over, docked, and they walked out on wooden planks to the vacant lot.

The owner of the barge informed Stewart that there were buses coming from Baton Rouge coming to pick up evacuees and he knew exactly where their location was. Juliet and her family had their doubts.

“We’re in an empty lot. We’re like, oh yeah, like somebody’s really gonna come pick us up. It took a while, but they did pick us up.”

From Baton Rouge, Juliet and her parents hotel hopped around Texas before her father and stepmother settled down in a trailer on his sister-in-law’s property on the northshore. After months of trying online, they were unable to locate their two chihuahuas or calico cat.

They never returned to Buccaneer Villa.

Finding Grace in the Change:

a message from the editor Cody Palazzolo

It would be pure mendacity to claim that I knew what I was walking into when I returned home for the first time after the storm. My family evacuated to my mother’s friend’s house in Folsom and from there we moved to Denver in a desperate attempt find an immediate sense of normalcy. A feeling that never came.

With the developing mind of a thirteen year old adolescent, I was exposed to new faces, teachers, and cultures every day in a city I knew hardly anything about. I knew New Orleans. I knew Chalmette. I knew Arabi. I barely knew Meraux and beyond, but this city in the mountains across the country was crushingly unfamiliar.

Our family in Colorado set us up with very comfortable accommodations. For the first time in my life, I had my own bedroom. Thanks to generous donations, I had money for clothes and was able to develop a sense of style (or at least whatever my favorite singer was wearing on the cover of Alternative Press at the time). I went to a school with a rich cultural arts program with more than one option for music class that didn’t involve marching band music, which I detested.

Still, I craved home. Even if I had to share a bedroom with my brother and wear the same school uniform all week, it was all I knew and wanted.

I remember Packenham Avenue being a colorful oasis. Every lawn was organically polished in vibrant green and healthy oak trees lined the street corners in picturesque Louisiana fashion. When I returned home in 2005, my vision of home was stained with what I first witnessed: a barren, sepia tinted wasteland. There was no sign life for miles.

The alleys in which I explored with my neighborhood friends had all been blocked by debris and sediment, the ground covered in a muck resembling what can be best described as muddy craters.

As the oil from the refineries crystallized into mud on top every surface, I knew it was over. My childhood was destroyed by God and greed.

At thirteen years old, you don’t think about how the oil refineries that surround your home proliferate the ecological destruction of the land you walk on. You don’t consider the farcical irony that the largest employer of your hometown is also responsible for destroying the only natural barrier between floodwaters and your home: the cypress marsh. It’s a funny way of getting cash in your pocket and right on out again.

Will the refineries ever face accountability? I seriously doubt it. As of May this year, the Senate voted to overturn an Environmental Protection Agency rule limiting the seven most hazardous air pollutants emitted by oil refineries. The odds of environmental agency aren’t in our favor.

Still, home is home. I didn’t move back to the parish to give businesses gold stars for air quality. I moved back for the people. I missed having authentic conversations with my neighbors. I missed the Staten-Island accents. I missed knowing that everyone around me understood a side of me that can only be understood if you rode out Hurricane Katrina and her aftermath. My peers seemed to have agreed when I asked if they felt connected to others who were also in their youth in St. Bernard Parish when Katrina hit:

Regardless of the empty property lots, the next “big one” anxiety, and the endless fight for protected wetlands, St. Bernard Parish is a place that is worth living in twenty years later. The main return pipeline was for the company that we still actively choose to keep. I don’t see that changing any time soon for any of us.

I’ve tried Denver, New York, and even life as a musical vagabond. This seems to be the only place that works. I’m perfectly content with that.